Case Study of Al-Bu Khassaf Women in Maysan, Southern Iraq

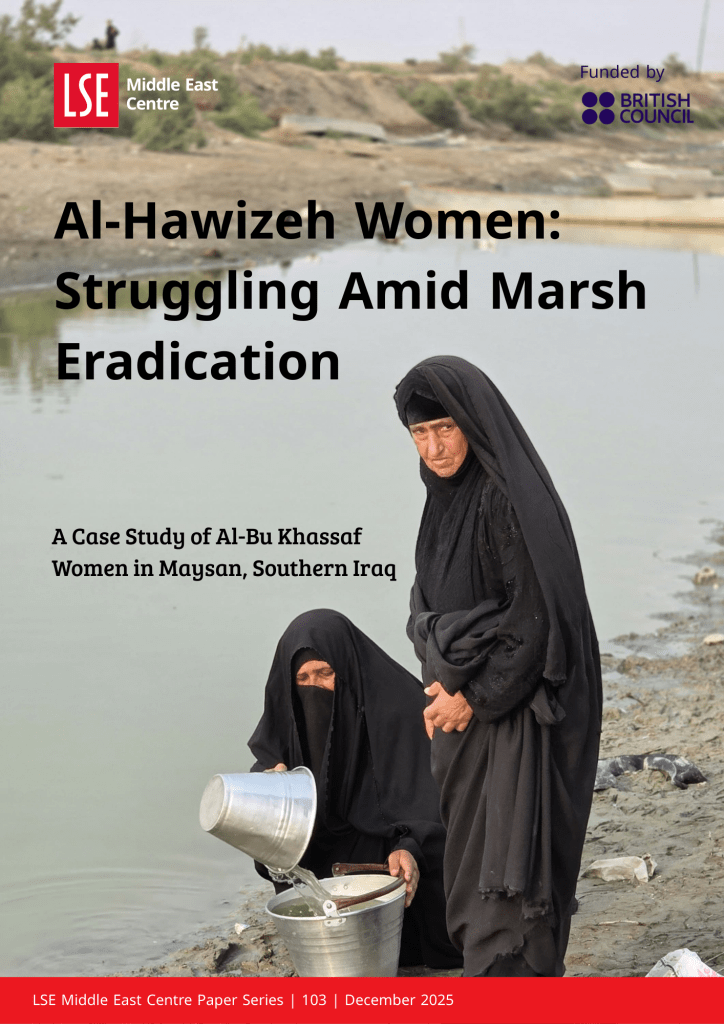

This paper examines the socio-ecological collapse of the Al-Hawizeh Marsh, through a gendered lens focused on the women of Al-Bu Khassaf village in Maysan. Based on field research and testimonies, it shows how drainage, oil extraction, and militarised governance dismantled marsh life. Women—custodians of endangered “Marsh Knowledge”—have shifted from central economic actors to conditions of poverty and dependency. The study calls for transboundary water governance, a halt to hydrocarbon expansion, demilitarisation, and formal recognition of women’s agency and heritage.

LSE Middle East Centre Paper Series | 103 | December 2025 – PDF

Abstract

This paper examines the socio-ecological collapse of the Al-Hawizeh Marsh, southern Iraq’s last surviving wetland, through a gendered lens centred on the women of Al-Bu Khassaf village in Maysan. Drawing on field research, interviews, and local testimonies, it documents how deliberate drainage, oil extraction, and militarised spatial governance have dismantled the ecological and cultural foundations of marsh life. The study situates women at the core of this collapse as the principal custodians of ‘Marsh Knowledge’: an inherited corpus of ecological, economic, and cultural practices now on the brink of extinction. It traces the shift from a participatory production model, where women’s labour sustained the collective economy, to a condition of severe livelihood erosion, dependency and impoverishment. These dynamics, the paper argues, reflect a deliberate reconfiguration of the marsh as an extractive and securitised frontier rather than a living heritage landscape. Beyond documenting loss, the study calls for urgent multi-level interventions: enforceable transboundary water governance, a moratorium on hydrocarbon expansion, demilitarisation, and the institutional recognition of women’s agency and intangible heritage. The women of Al-Bu Khassaf thus emerge as both witnesses and resisters within Iraq’s broader landscape of environmental and developmental failure.

Introduction

The Al-Bu Khassaf village, in the Bani Hashim sub-district of Maysan Governorate (southeast Iraq), currently home to between 150 and 200 families, is one of the few remaining inhabited areas in the former body of water known as the Al-Hawizeh Marshes. While facing the imminent threat of obliteration, Al-Bu Khassaf also stands as a powerful example of a marginalised marshland community, where the necessities for survival are destroyed daily under a security siege in order to force the residents to emigrate.1

The women of Al-Bu Khassaf struggle daily necessary to survive and maintain their traditional marsh values as they are disempowered in the face of significant challenges: ecological destruction wrought by drought, deliberate national and regional policies, and the expansion of oil extraction. These challenges threaten to erase the existence and culture of an ancient community whose livelihood and survival have always been tied to its environment, who now face the loss of a deeply historic landscape.

Al-Hawizeh: The Eradication of the Ecosystem

Satellite images2 in 1967 depicted the old Al-Hawizeh Marsh as a vast and expansive body of water, interconnected with the adjacent southern Iraqi marshes and extending across the border into Iran, where the two countries’ shared wetland of Hoor al-Azim is located. Between 1984 and 2015, Iraq lost one-third of its permanent water surfaces, while its historic marshlands shrank by 86 percent.3 The most significant loss was concentrated in the submerged areas of Al-Hawizeh.

Before its current deliberate drainage, the Al-Hawizeh Marsh, covering a total area of 1,377 km² (30 km wide and 80 km long), representing the central component of the rare national ecological and hydrological system, as ‘the largest of its kind in the Middle East and West Eurasia.’4 The Iraqi side of Al-Hawizeh previously depended on the Iranian Karkheh River for most of its essential water supply. Additional inflows came through the national secondary tributaries of the Tigris.

The marsh population in Iraq’s wetlands decreased from half a million in the 1950s5 to around 20,000 after large-scale desiccation in the 1990s.6 Post-2003, the population recovered slightly to 40,000.7 A large number were once again forced to leave the marshes after the failure of the ‘Marshlands Recovery Program’; particularly between 2021 and 2023, when ‘more than 200 families from four villages were displaced, with no government assistance.’8

Iran gradually cut off the marsh’s water supply from the Karkheh River: first in 1991, then again in 2001, and finally in 2011, when the flow was stopped entirely. Nationally, the Iraqi government began its own measures in the summer of 2021, followed in February 2022 by the construction of a massive earthen barrier under the pretext of curbing drug smuggling,9 while simultaneously reducing water releases to below 50 m³/s.10 As a result, Al-Hawizeh has lost more than 85 percent of its area since 2021,11 with dust replacing water and desert plants taking the place of reeds,12 leaving the marshland completely dry by August 2025.13

Although officials deny any impact from petroleum activities on the marshes, framing this position within a misleading environmental doctrine,14 oil projects – such as the 2009 second round and the 2023 fifth round of oil licensing – have gradually eroded and devastated Al-Hawizeh. UNESCO’s World Heritage Centre, in its 2025 periodic review,15 emphasised that oil projects are incompatible with World Heritage status. UNESCO may, in its upcoming 2027 periodic review, remove Al-Hawizeh and other Iraqi wetland sites from the List. This risk is heightened in light of the joint recommendation of the Ramsar Advisory Mission in coordination with the Center for Restoration of Iraqi Marshes and Wetlands (CRIMW), which called for establishing a mechanism to delist Al-Hawizeh from the Montreux Record16 due to ongoing extraction activities and oil development.17

Methodology

This research paper aims to explore the challenges posed by the devastating environmental impact on the Al-Hawizeh Marsh women. Al-Bu Khassaf village was selected as a case study. The analysis relied on a combination of qualitative research methods, including a direct field visit, two focus group discussions (FGDs) with the village’s women and men, and a three-month collaboration (June–September 2025) with a local volunteer social network to facilitate access to the field and ensure broader representation of women’s views.

A core questionnaire was designed, consisting of 22 questions,18 aimed at identifying the drivers of environmental degradation as well as the extent of their impact and the response. This mechanism resulted in 26 interviews conducted in person or by phone, including 12 with women and 10 with men, in addition to four interviews with two government officials, a veterinarian, and a researcher interested in the history of the marshes. Part of the interview findings are presented in this paper as firsthand testimonies.

The Lost Heritage: Marshland Women’s Knowledge

Today’s older Marsh women represent a continuation of the generations that preceded them, standing as the last living link to that heritage. They are also the final bearers of the accumulated ‘marsh knowledge’, passed down orally. Together with younger and transitional generations, they confront the profound loss of their ecological homeland, marshland identity, and the cultural fabric that once defined their existence. This decline has given rise to a ‘transitional generation’, such as Safiya Hashim, a 17-year-old high school student, alongside an even younger ‘generation of rupture’ that has no living connection or are increasingly moving away from marshland life.

In Al-Bu Khassaf, Safiya receives this marsh knowledge from her mother. She explains, ‘Life in the marshland is difficult, especially with the drought. We put in double the effort to care for the buffalo, gather fodder, and to participate in generating income for the family.’ Yet, Safiya is concerned that she will lose the ability to pass on her knowledge if complete drying occurs and her family is forced to leave.

The older marsh women have endured dramatic environmental changes that struck their ancestral homeland over the past few decades. They resisted these transformations, often refusing to accept new ways of living that clashed with their deeply rooted marshland knowledge. By contrast, the ‘transitional generation’ and the emerging ‘generation of rupture’ are more inclined to accept such changes, as they are already partially or entirely disconnected from their mothers’ environment. This acceptance, however, comes at the cost of losing the cultural heritage.19

Marsh Knowledge: Women’s Inherited Skills

‘Marsh knowledge’ refers to the traditional ecological skills and cultural practices developed by marsh women over millennia, whether in Al-Hawizeh or across Iraq’s other wetlands. Women have built a heritage of knowledge and developed exceptional resilience over centuries in a harsh environment fraught with risks, living within a vast ecosystem that is teeming with predatory and venomous animals, insects, microbes and pathogens. Consequently, they cultivated valuable expertise in protecting themselves and their families. Simultaneously, they preserved intricate forms of household care and developed notable skills in negotiation and trading, which enabled them to market their products in nearby towns and urban centres.

Over the centuries, marshland women have accumulated a rich body of knowledge and skills, includes unique dialects, oral traditions of storytelling, poetry, and lamentation, as well as culinary practices, dairy production, the traditional AlKhourit sweets,20 fish drying, and large animal husbandry, such as for water buffalo. In addition to this they have mastered the use of medicinal plants, handicrafts, and sustainable environmental practices like using animal waste as fuel.

Marsh women also possess remarkable knowledge in the use and preparation of natural materials for beauty and traditional practices. These include the AlSowayka, a tobacco-like herbal mixture used for relaxation; AlDeirum, applied as a natural lipstick; and local tattooing, known as Al-Dakk, which serves as an expression of women’s agency and social identity. Marsh women have developed a profound understanding of seasonal cycles, tracking weather changes, floods, droughts and agricultural rhythms, as well as fishing seasons and the collection of reeds and grasses. They possess precise knowledge of the intricate network of waterways within the marshes and display remarkable skill in navigating (AlMashahif) with confidence and accuracy without navigational tools, as they traverse the vast and branching delta of the wetlands.

Although women are the primary custodians of this unique, undocumented body of knowledge, reflecting the living memory of the original marshland ecosystem,21 there is no governmental or UN-led programme to safeguard it as intangible cultural heritage. Even Iraq’s sole national law on the protection of antiquities and heritage (2002)22 makes no reference to marshland traditions. Likewise, international initiatives to review or amend the law, such as the 2022 advisory mission of the European Union Advisory Mission in Iraq (EUAM),23 have overlooked the heritage of the marsh Arabs entirely.

Social Leadership: Participatory Production Model

The knowledge and skills of the marsh women would lose their value entirely if the marshes themselves were to disappear. Moreover, the women’s marshland knowledge is intrinsically tied to the raw materials and tools that the marsh provides in a sustainable and cost-free manner.

Across generations, women have long known how to maintain balance between sustainability and self-sufficiency, preserving the marsh’s practical and emotional value. In return, the marsh has elevated their social standing, positioning them as indispensable actors within the cooperative economic cycle, equal in status and importance to men. Within this ecologically interdependent economic and social system, women embody cultural capital and are the principal leaders of ‘the participatory mode of production’, with ‘family’ as its central nucleus; ‘marsh women are workers by nature, sharing responsibilities equally alongside men.’24

One of the Al-Bu Khassaf women explained, ‘Before the drought struck in 2021, we all worked together as a family. I used to help my husband set the fishing nets at night and collect them at dawn. Every day, we earned between 50,000 and 200,000 dinars.’25 Another woman described how shared labour once defined their existence: ‘We lived on what the marsh provided – fishing, selling milk and dairy products. Our daily income ranged from 150,000 to 200,000 dinars, which was enough to cover our needs comfortably.’26

One significant role involved social solidarity (which has an unseen economic dimension): managing charitable donation funds that are often allocated to help low-income families and to hold seasonal religious celebrations such as Ashura. Umm Rasool previously undertook this role before the drought:

Each season, we collected between three and four million dinars from our savings to assist the poor and organise the Ashura rituals. We purchased food, livestock, and other supplies, which we distributed freely among participants. However, since the onset of the drought, we have been unable to contribute due to worsening economic hardship.27

This symbiotic role underscores the cultural significance and ‘moral power’28 of women as social leaders, who direct their incomes not only to benefit their families but also contribute toward the broader public sphere to which they belong.

Women without Marshes: Erosion through Impoverishment

In February 2020, the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) and the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) proposed the term ‘the stayees’29 to describe those who insist on remaining in their lands despite severe water scarcity and environmental destruction across the marshes of Basra, Maysan, and Dhi Qar. The concept highlights the growing fragmentation of marsh families into three groups: displaced, migrant job seekers, and stayees. Division poses significant long-term social risks to the cohesion and future rebuilding of marshland society.30

Al-Bu Khassaf’s inhabitants believe31 that remaining in their homes is a peaceful means of pressuring the government. Women, in particular, firmly refuse the prospect of migration. As they explain: ‘We cannot afford the relocation costs. We have no alternative sources of livelihood, no salaries, no health insurance, and no unemployment benefits. We cannot survive dispersed and homeless.’32

The deepening economic crisis has increasingly pushed marsh women to depend on the meagre income sent back by male family members who have left to seek work in urban areas or to join the security forces and military. This survival dynamic has placed an even greater burden on the women left behind, who must manage households alone in times of acute hardship.33

The restructuring of the marshland area has profoundly affected the sustainability of women’s livelihoods, contributing to the erosion of their community roles and limiting their independence. Compared to the pre-drought era of the ‘Participatory Production Model’, their roles are now ‘increasingly confined to household tasks, while opportunities to generate income through traditional skills have become extremely limited.’34 Al-Bu Khassaf’s women reported35 that their primary source of income is now handicrafts such as basket weaving, but their products are often sold for less than 500 Iraqi dinars (about £0.28), reflecting the limited market value of their work.

The women of Al-Bu Khassaf emphasise the intensifying ‘severity of environmental impact’,36 which is rooted not in climate change but in the compounded effects of harmful governmental and industrial practices: firstly the deliberate drainage and ecological erasure of the marshes, and secondly the securitisation of the area, aimed at reshaping it for extractive commercial purposes, border control, and anti-narcotics operations.

The ongoing militarisation of the marsh represents one of the most damaging interventionist policies impacting women, manifested in its division into ‘spaces of security’ that are subjected to stringent spatial management strategies. Interventionist security and spatial policies have categorised women as a security threat, effectively restricting their mobility within their native environments. Al-Bu Khassaf’s women have been prohibited from reaching the nearby Umm al-Ni’aj pond or accessing the remaining reed stands located deep within the now-dry marshlands.37 A woman from Al-Bu Khassaf explained, ‘Due to the security restrictions, we have lost everything. Our buffalo are hungry and sick. We are trying to take them to the Umm al-Ni‘aj pond, but we are prevented; the army blocks us securely and deprives us of the reeds and the water.’38

The securitisation of the marshes has fragmented the area into restricted zones, enclosed by earthen embankments and barbed wire, and controlled through checkpoints where individuals are subjected to thorough inspections and required to surrender their identification. Entry also depends on special security permits that must be renewed every six months, available only to a limited number of male residents. Authorities justify these restrictive measures as ‘necessary to curb drug smuggling across the Iranian border’,39 and also argue that ‘the lack of female security personnel makes it impossible to search women’.40

The dynamics of population control within Al-Hawizeh reveal a clear gender-based discrimination specifically targeting women, with the deliberate aim of ‘forcing families to migrate through policies of impoverishment and starvation.’41 Some families have no male breadwinners and ‘rely entirely on women for income, but the security restrictions have left these women in constant suffering and extreme poverty.’42

Al-Bu Khassaf: Interconnected Developmental Failure

Al-Hawizeh, including Al-Bu Khassaf, suffers from interconnected developmental failures and an acute lack of basic infrastructure to support daily life, including the absence of safe drinking water, electricity supplies, transportation routes, waste collection and sewage treatment facilities, schools, health centres, or even a local police station.

Water scarcity

Abandoned fishing nets and tools, neglected and unmaintained mashahif, and constantly angry buffalo symbolise the devastating impact of drought on the Al-Hawizeh community. As the researcher who visited the village concluded: ‘The suffering here is far deeper than words can describe. Women struggle daily to secure potable water or for bathing children, free from chemical pollutants, disease agents, or animal carcasses. The buffalo are going blind, developing severe skin diseases, and dying in place because of contaminated water.’43

Drought does not only mean the death of the marshes; it signals the collapse of the area’s economic resources, which deepens household vulnerability, as women must invest increasing time and hardship in caring for buffalo, whose milk had long been a vital source of income. Before deliberate drainage began in 2021, ‘one marsh village produced around 2,200 litres of milk per day. After the drought, production dropped to just 150 litres.’44

Seeking slightly cleaner water, women are forced to walk long distances every day, particularly in the summer, when temperatures soar over 50°C. Many still rely on polluted and unsafe sources for their daily needs, exposing themselves and their families to serious health risks. Several women reported45 that the daily use of stagnant, foul-smelling green water had caused widespread skin, intestinal diseases, nausea and vomiting. To secure potable water, families are forced to purchase reverse osmosis (RO) water every day, an added economic burden that drains their already scarce resources, leaving them with less to cover other essential needs.46

Education and Transportation

The region’s economic failure has reduced families’ ability to afford girls’ education or provide school supplies for children, leading to increased dropout rates. The lack of post-primary schools also forces families to limit their children’s education to this level. Transportation is also a structural challenge that limits girls’ ability to continue their education to higher levels.

Safiya Hashim, for instance, travels nearly 30 km every day to attend high school. ‘I have to walk one km just to reach the nearest point where a vehicle can pick me up,’ she explained. ‘All the children from the village, boys and girls, ride in the same car each day. The condition of the roads is so poor that an accident could happen at any time.’

Police Service

The absence of a local police station in Al-Bu Khassaf compounds women’s vulnerability, particularly in cases of gender-based violence. Social norms often normalise domestic abuse as a ‘traditional way of life,’ rendering them ‘silent victims’ with no safe mechanisms for reporting it.

As a result, in the absence of explicit recognition and the lack of reported cases in government records, the potential social harms directed at women remain hidden. The director of the Maysan police chief’s office says, ‘As long as there are no official reports from women, we cannot claim to have any recorded incidents of this kind.’47 Cultural sensitivity has severely limited field access to potentially abused women.

Health Care

The health infrastructure in Al-Bu Khassaf is virtually non-existent, lacking any government-provided care or facilities to offer women assistance in cases of injury, accidents, or mental health crises; they are worn down by the daily hardships they face without adequate support or care. Since 2014, the authorities have repeatedly closed the area’s only marginal primary health centre, citing resource shortages, and it now provides no meaningful services. Residents believe that ‘the actual purpose is to deprive them of services in order to force them to migrate.’48

It also has no veterinary clinic to treat buffalo and other animals suffering from severe skin diseases. Since women are the primary caregivers for livestock, this exposes them to serious risks, including attacks by distressed buffalo weakened by thirst and extreme heat. As the veterinarian explained, ‘under drought and rising temperatures, buffalos’ stress levels rise sharply, making them aggressive and dangerous toward the women who care for them.’49

Conclusion

This case study contributes to the literature on the sociology of environmental and social problems by concluding that decision-makers face an ethical and practical test: whether to preserve the conditions of life or legitimise the demise of the marsh community. Drawing on field visits, direct interviews, and the tracking of open-source data, the plight of Al-Hawizeh’s inhabitants is not a transient environmental incident but rather a complex structure of impoverishment, driven by systematic desiccation, the expansion of hydrocarbon extraction, and spatial militarisation, which undermine the conditions of life and re-engineer the social domain, redistributing the cost to women in particular and reducing their productive roles to the confines of low-return domestic work.

Multi-Level Public Responses

First: National or regional transboundary water quotas with legal guarantees, to prevent the deliberate drying up of marshland.

Second: Immediate halt to any extractive activity with the possibility of any resumption only after binding ecological impact assessments are imposed.

Third: Lifting security restrictions that target women and replacing the management of ‘security spaces’ with participatory local governance systems.

Fourth: Re-establishing basic services as a survival structure, rather than a developmental privilege.

Fifth: A national programme to document and preserve local women’s intangible heritage (‘marsh knowledge’).

Sixth: Acknowledging women’s agency in the marshlands and including them in adaptation plans, empowerment initiatives and negotiation and policymaking.

Seventh: Allocating a budget for marsh women’s empowerment as part of future climate change initiatives.

- Phone interview with a village activist, August 2025. ↩︎

- Eoghan Darbyshire, ‘The Past, Present and Future of the Mesopotamian Marshes’, Conflict and Environment Observatory, September 2021. Available at: https://goo.su/5RtCKG (accessed 21 November 2025). ↩︎

- Michael Mason, Zeynep Sıla Akıncı, Arda Bilgen, Noori Nasir & Azhar Al-Rubaie, ‘Towards Hydro-Transparency on the Euphrates-Tigris Basin: Mapping Surface Water Changes in Iraq, 1984–2015’, LSE Middle East Centre Paper Series 74, October 2023. Available at: https://goo.su/NyoPeJK (accessed 21 November 2025). ↩︎

- Hassan Partow, ‘The Mesopotamian Marshlands: Demise of an Ecosystem’, Division of Early Warning and Assessment United Nations Environment Programme Nairobi, Kenya (2001). ↩︎

- Shaker Mustafa Salim, Al-Chibayish: An Anthropological Study of a Village in the Marshes of Iraq (Baghdad: Al-Ani Press, 1970) [in Arabic]. ↩︎

- John Fawcett & Victor Tanner, ‘The Internally Displaced People of Iraq’, The Brookings Institution–SAIS Project on Internal Displacement, October 2002. Available at: https://goo.su/ZOq03f (accessed 21 November 2025). ↩︎

- , ‘Report of the Special Committee on Environmental Cooperation for Iraq’, Special Committee on Environmental Cooperation for Iraq (SCECI), March 2006. Available at: https://goo.su/6tqtD (accessed 21 November 2025). ↩︎

- Phone interview with an environmental activist from Al-Bu Khassaf, August 2025. ↩︎

- ‘Iraq Decides to Build an Earthen Berm on the Border with Iran to Curb Drug Smuggling’, Kuwait News Agency, 15 February 2022 [in Arabic]. Available at: https://goo.su/GzeY2Uv (accessed 21 November 2025). ↩︎

- Hoor al-Azim, ‘A Biography of Drought and Drainage’, Al-Alam Al-Jadeed, 25 July 2021 [in Arabic]. Available at: https://goo.su/kSV0 (accessed 21 November 2025). ↩︎

- Adam Ali, ‘Oil Exploration Threatens to Remove the Hawizeh Marsh from the World Heritage List’, Daraj Media, 4 June 2025 [in Arabic]. Available at: https://goo.su/QqbFn (accessed 21 November 2025). ↩︎

- ‘Climate Crisis: Drought Replaces Water in Iraq’s Marshlands’, UN News, 15 August 2023 [in Arabic]. Available at: https://goo.su/DRgIyL (accessed 21 November 2025). ↩︎

- Phone interview with a government employee in the Water Resources Department in Maysan Governorate, August 2025. ↩︎

- Safaa Khalaf, ‘Iraq at the COP: A Misguided Environmental Doctrine’, Arab Reform Initiative, January 2025. Available at: https://goo.su/M5BLV (accessed 21 November 2025). ↩︎

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre, ‘The Ahwar of Southern Iraq: Refuge of Biodiversity and the Relict Landscape of the Mesopotamian Cities (Iraq), Decision 47 COM 7B.61’, 47th Session of the World Heritage Committee (2025). Available at: https://goo.su/fwgw8OB (accessed 21 November 2025). ↩︎

- ‘The Montreux Record and the Ramsar Advisory Missions’, Ramsar Information Paper no. 6, 2007. Available at: https://goo.su/ByEf57 (accessed 21 November 2025). ↩︎

- Clayton Rubec and Lew Young, ‘Report on a Ramsar Team Visit to the Al-Hawizeh Ramsar Site’, Secretariat of the Convention on Wetlands, February 2014. Available at: https://goo.su/AZXQ6B (accessed 21 November 2025). ↩︎

- The core questionnaire [in Arabic]. Available at: https://goo.su/e13X7 (accessed 21 November 2025). ↩︎

- Interview with an activist in Maysan, July 2025. ↩︎

- AlKhourit is a marsh sweet made from a yellow cellulose substance extracted from the nectar of papyrus flowers. ↩︎

- Nadia Al-Mudaffar Fawzi, Kelly P. Goodwin, Bayan A. Mahdi & Michelle L. Stevens, ‘Effects of Mesopotamian Marsh (Iraq) Desiccation on the Cultural Knowledge and Livelihood of Marsh Arab Women’, Ecosystem Health and Sustainability 2/3 (2016): e01207. Available at: https://goo.su/Cdg0X3 (accessed 21 November 2025). ↩︎

- ‘Antiquities and Heritage Law No. (55) of 2002’, Iraqi Gazette, Issue 3957, 18 November 2022, p. 566 [in Arabic]. Available at: https://goo.su/HauLAWX (accessed 21 November 2025). ↩︎

- ‘Legal Aspects of Cultural Heritage Protection’, European Union Advisory Mission in Iraq (EUAM), March 2022 [in Arabic]. Available at: https://goo.su/ShUhBo (accessed 21 November 2025). ↩︎

- Interview with an activist in Maysan, July 2025. ↩︎

- Interview with a woman from Al-Bu Khassaf, July 2025. ↩︎

- Interview with a woman from Al-Bu Khassaf, July 2025. ↩︎

- Field interview with Umm Rasoul, July 2025. ↩︎

- Interview with an activist in Maysan, July 2025. ↩︎

- ‘When Canals Run Dry: Displacement Triggered by Water Stress in the South of Iraq’, The Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre and the Norwegian Refugee Council, February 2020. Available at: https://goo.su/XDW08 (accessed 21 November 2025). ↩︎

- Safaa Khalaf, ‘Iraq’s Water Crisis: Climate Change Leads to Migration and Civil Strife’, Candid Foundation, 24 December 2021. Available at: https://goo.su/jpzgn (accessed 21 November 2025). ↩︎

- FGD with men of Al-Bu Khassaf, July 2025. ↩︎

- FGD with women of Al-Bu Khassaf, July 2025. ↩︎

- ‘Ahwari Women: The Beating Heart of the Iraqi Marshes’, United Nations Development Programme, 8 March 2021. Available at: https://goo.su/zVZ6YX3 (accessed 21 November 2025). ↩︎

- Fawzi et al., ‘Effects of Mesopotamian Marsh (Iraq) Desiccation on the Cultural Knowledge and Livelihood of Marsh Arab Women’. ↩︎

- FGD with women of Al-Bu Khassaf, July 2025. ↩︎

- Safaa Khalaf, ‘Climate Change and the Water Crisis in Iraq: Indicators of Vulnerability and the Severity of Environmental Impact’, Assafir, 21 November 2022. Available at: https://goo.su/pNo5G (accessed 21 November 2025). ↩︎

- ‘Army forbids women to approach Iran’s borders’, +964 News Agency, July 2024 [Arabic]. Available at: https://goo.su/Bqbr9zJ (accessed 21 November 2025). ↩︎

- Interview with a woman from Al-Bu Khassaf, July 2025. ↩︎

- ‘Al-Huwaiza Dam: Was the marshland drained and “dispossessed” for security purposes?’, Baghdad Today News Agency, July 2025 [Arabic]. Available at: https://goo.su/AWq1nX (accessed 21 November 2025). ↩︎

- FGD with men of Al-Bu Khassaf, July 2025. ↩︎

- Interview with an activist from Al-Bu Khassaf, July 2025. ↩︎

- Interview with a man from Al-Bu Khassaf, July 2025. ↩︎

- Video note by researcher who visited Albu Khassaf, July 2025. ↩︎

- Interview with an activist in Maysan, July 2025. ↩︎

- Interview with women from Al-Bu Khassaf, July 2025. ↩︎

- Interview with women from Al-Bu Khassaf, July 2025. ↩︎

- Interview with an activist in Maysan, July 2025. ↩︎

- Phone Interview with an activist in Maysan, August 2025. ↩︎

- Phone interview with a veterinarian, August 2025. ↩︎